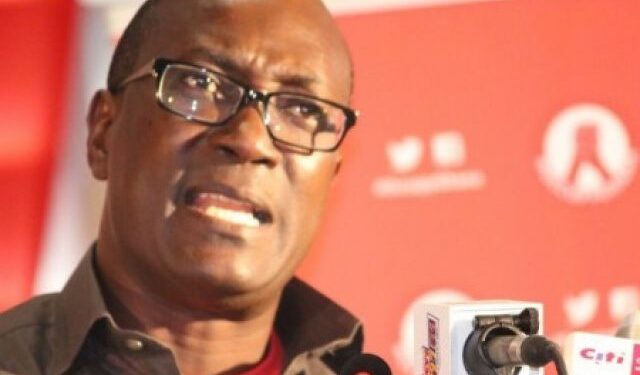

The Executive Director of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) Professor H Kwasi Prempeh has proposed a nonpartisan presidency for the Republic of Ghana.

He explained that the experience so far leads him to the conclusion that the partisan presidency is the principal millstone around the neck of the people, poisoning Ghana’s elections and institutions, retarding the governance and development aspirations, and putting the democracy in peril.

“Nothing about representative democracy, including democracy with parties, says we must have parties competing for control of both legislative and executive power.

“After all, we don’t allow parties to compete for seats on the judiciary, the third branch of government, even though nothing about representative democracy says that can’t be done (e.g., some states in the United States choose their judges through partisan elections, which is, of course, a terrible idea),” he wrote in his proposal.

PUTTING COUNTRY FIRST: THE CASE FOR PRESIDENTIALISM WITHOUT PARTIES

Taking on board the lessons of our political experience as a country, I think it’s time to try some deep constitutional innovation to save our country and its fragile democracy. To do this, we must seize the bull by the horns. And that, for me, means overhauling the presidency–specifically, how we choose our presidents.

The binary partisan fight for exclusive control of the presidency is at the root of much, if not all, that is wrong with our politics and governance. The combination of presidentialism and a binary, winner-take-all partisan politics yields toxic results in our parts. The remedy? Decouple the one from the other; take political parties out of the presidency. Let’s choose our presidents on a no-party/nonpartisan basis, restricting our political parties to parliamentary elections.

We must design our political institutions, starting with the constitution, to suit our experiences and circumstances and help address our peculiar problems as a country. Our experience so far leads me to the conclusion that the partisan presidency is the principal millstone around our neck, poisoning our elections and institutions, retarding our governance and development aspirations, and putting our democracy in peril.

Nothing about representative democracy, including democracy with parties, says we must have parties competing for control of both legislative and executive power. After all, we don’t allow parties to compete for seats on the judiciary, the third branch of government, even though nothing about representative democracy says that can’t be done (e.g., some states in the United States choose their judges through partisan elections, which is, of course, a terrible idea). Similarly, partisan elections need not be extended to elections for presidential or executive office. In fact, the idea of chief executives who are elected on a nonpartisan basis is not uncommon at the town or local government level in many democracies. There is no reason why we couldn’t have it or shouldn’t try it at the national level.

The legislature, not the executive, is the historical home of political parties. And parliament is still where political parties properly belong in a representative democracy, because that is where rival aggregations of interests in the society can deliberate and compete with one another over ideas and ideologies and for control of legislation. In contrast, the president, the one office that is supposed to represent–and hold together–the whole nation, cannot function properly as a unifying or national figure if captured and controlled by or beholden to one party. In our experience, a president who is elected to office as the candidate of a party will put his or her party first, over and above the interest of the nation.

Our experience in this 4th Republic also shows that the separation of powers and checks and balances that is supposed to define the relationship between the legislature and the executive is merely theoretical and breaks down in practice, undercutting Parliament’s executive oversight role and reducing it to a rubberstamp, when a partisan president and the majority in Parliament are of the same party. On the flip side, where a partisan president faces a Parliament that is either dominated by the rival party or has a shifting partisan majority, prospects for partisan gridlock in government are heightened, raising governability challenges. As our experience attests, neither scenario is good for good governance.

These weaknesses of party-based presidentialism are, of course, not peculiar to Ghana; they are experienced, in varying degrees, also by countries where, like Ghana, two rival and polarizing parties dominate the electoral competition for both the legislature and the presidency. Such countries, too, could benefit from rethinking this model of party-based presidentialism. But my primary and immediate concern is Ghana. Thus, what I propose here, while relevant or applicable to similar contexts elsewhere, is meant as a Ghanaian solution to a Ghanaian problem.

Some of our political parties and their partisans will, of course, object and are likely to lose interest in the whole political “game” once the “crown jewel” is taken off the table. But why? The truth of the matter is that our parties are not, and do not function as, classical political parties. If they were, they would actually welcome and love the idea of competing against their rivals for control of legislative agenda, including budgets. But our parties aren’t interested in that; legislative power alone is not good or attractive enough for them. In fact, they see legislative power only or primarily as a means to an end. It is the presidency and related executive power–and, with it, access to the public resources–they really want. Being able to control legislative power concurrently is a big plus mainly because it enables their exclusive hold on the presidency to be firm and complete. And that is why when they have gained control of legislative power, they simply donate it all back to their partisan president in return for patronage and a share of the spoils of executive office. So if neither party can have the presidency, it would indeed be a huge material loss and disincentive for them, but their loss, in that regard, should be our collective gain as a nation. Other parties and politicians more interested in what they can contribute to our politics and governance than in what they can get from it are likely to emerge and enter Parliament.

Apart from addressing the toxic partisanship of our contemporary politics, which is centered around the do-or-die capture of the presidency for the advancement of partisan and related private interests, the idea of a nonpartisan president is also more in consonance with our traditional African governance traditions than the conventional partisan presidency, which is a borrowing from non-African political traditions. Thus, those of you who say you want a political system that is modelled after our indigenous governance traditions and is, thus, more consensus-, as opposed to conflict-, driven should like this proposal, particularly with the additional reforms proposed below.

The nonpartisan presidency proposal would come with the following companion reforms, among others:

- Presidential campaigns wil be state-funded: No political party may donate funds to or sponsor or endorse a presidential candidate, and it would be unlawful and grounds for disqualification for a candidate to receive money from a political party or a foreign source. Campaign spending will be strictly regulated and audited, including strict limits on and standardization of the size, number and location of candidate bill boards. NCCE will be responsible for organizing televised and live-streamed debates in district townhalls across the country, plus two national debates; two scheduled national addresses on radio and TV per candidate.

- To be eligible to contest the presidential election, a candidate must secure the endorsement of a specified minimum number of registered voters or of citizens qualified to register to vote, distributed in a specified proportion across the regions of the country. No more than x number of candidates in total will be allowed on the ballot. A run-off between the two top candidates will be held if no candidate receives more than 51% of the vote in the first round.

- All candidates for president (together with their deputies) shall publicly declare their assets and liabilities and disclose their sources of income and have these independently verified (by the Auditor-General) BEFORE they can qualify to contest. The candidate who is elected president, as well as his or her deputy, Ministers and all other appointees, shall update their verifiable net worth disclosures once every year or two years and upon leaving office. The declarations will be publicly accessible. Strict conflict of interest and anti-nepotism rules will bind all holders of public office, including the President and his or her appointees.

- To be eligible for state funding and to participate in campaign activities, a candidate must produce a manifesto whose content must be shown to be in alignment with the constitution’s directive principles of state policy and any national development plan approved by Parliament. Parliament will monitor and ensure implementation of the plan-aligned manifesto in the period after the elections.

- Each presidential candidate will name a deputy presidential candidate or running mate. President and deputy cannot be of the same sex.

- Upon election, the deputy president will become an ex officio voting member of Parliament with responsibility for leading government business in the House.

- A President may choose no more than 25% (one-fourth) of his or her Ministers from persons belonging to the same political party. Most ministers would thus have no real party affiliation. The number of Ministers will be capped by an Act of Parliament. Also, no new Ministry can be created except by an Act of Parliament.

- No MP shall serve concurrently as Minister or hold any office in the executive branch or public services, but the Majority and Minority Leaders of the House will have the right to participate in all meetings of the Cabinet.

- The tenure of the President will be limited to a single nonrenewable term of six years. Parliamentary and local government elections will, however, be held once every four years.

- No presidential appointment of mayors or MMDCEs. Mayors in regional capitals and metropolitan and municipal districts will be elected by the local population on a nonpartisan basis; parties will be free to compete in local town council/assembly elections. In effect, elections for executive office, both local and national, will be nonpartisan, while elections for legislative office, both local and national, will be open to parties. The number of districts will be cut down substantially using a threshold population size as basis. Creation of new districts will require a two-thirds majority of Parliament.

- Appointment to directorships and management of state-owned enterprises will be done through open, competitive, meritocratic recruitment and selection processes, with their tenure and retention tied to performance-based with clear deliverables and targets. Persons holding office in a political party will be ineligible for appointment to such positions.

- The Office of the President will be administered by a Chief of Staff and two deputies appointed by the President, with the assistance of a restricted number of administrative aides and policy advisors. All other presidential staffers will be civil/public servants and technocrats seconded by the Public Services Commission and the NDPC.

- More companion reforms to follow: council of State; attorney-general; electoral commission; judiciary; public lands and natural resources; etc.